26 Apr SANSA to build its very own square kilometre array

SANSA will be building their very own square kilometre array out in the Karoo, but rather than the radio waves the now-famous SKA will collect from outer space, this one will collect electrical field measurements from highveld thunderstorms. These electrical field measurements will help scientists better understand the elusive phenomenon known as sprites.

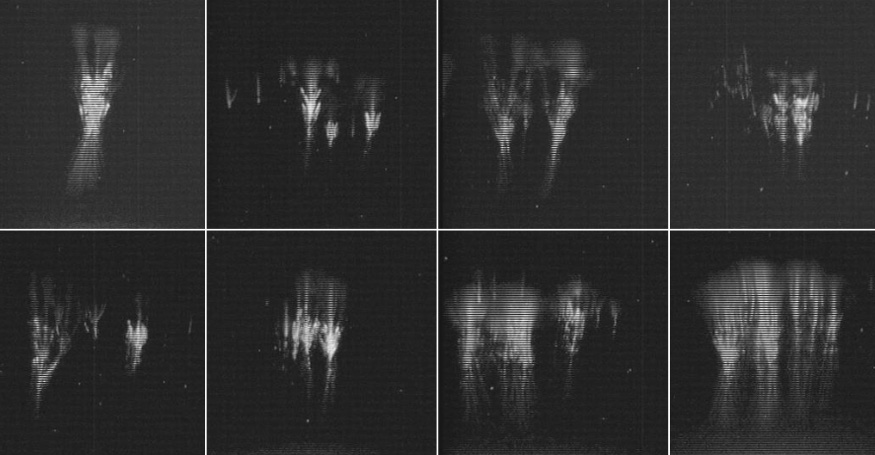

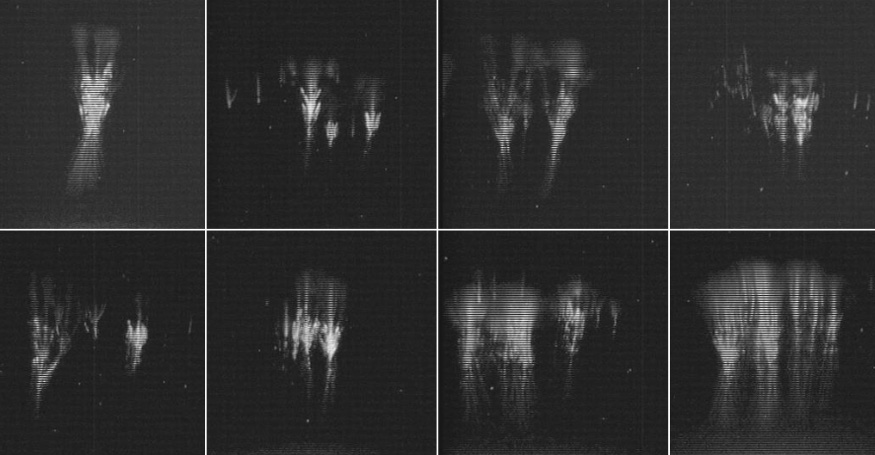

A few of the sprites captured by Prof Mike Kosch and his team during their recent research trip to the Northern Cape. Sprites are natural phenomena that occur above thunderstorms, caused by large electrical fields generated by lightning strikes.

Sprites are brief, beautiful flashes of light in the upper atmosphere, above thunderstorms, triggered by the huge electrical fields created when lightning strikes the ground.

These electrical fields cause a high-altitude gas discharge, and can be caught on camera if you know where to look.

“During last year’s sprite campaign we tested out an electrical field receiver, and this time around we took actual measurements,” says Prof Mike Kosch, Chief Scientist at SANSA and lead researcher on the South African sprites project.

“The research team measured the electric fields of the sprites while taking optical measurements at the same time. That’s never been done before.”

One of Kosch’s students recently submitted his PhD thesis; another student his MSc thesis on the subject, and has now started a PhD to analyse this combined data. But Kosch and his colleagues have even bigger plans.

“In 2020, we’re going to build our own SKA out in Carnarvon: a square kilometre array of electric field receivers. With an array, we can work out the direction of arrival of the signal and get a better understanding of how sprites are formed.”

The array comes from a long-time collaborator on this work, Dr Martin Fullekrug of the University of Bath. He is the only researcher in the world with the right equipment to take these measurements.

This was the fourth time that Kosch and his team have taken a field trip to the Northern Cape on a sprite-hunting expedition. They go every summer, and this year’s efforts provided a wealth of sprite images (over 360 images were captured over three weeks) and data.

This year, they tried something more ambitious: simultaneous capture of a sprite from two different locations.

“The team set up cameras near the SKA site in Carnarvon, and at SANSA’s newly-established Optical Space Research (OSR) Laboratory in Sutherland about 200kms away,” Kosch explains.

The OSR Laboratory is SANSA’s field office for sprites research, and houses some other research equipment including a space debris tracking station operated by the German Space Agency, DLR. “We took bistatic measurements – that means we tried to film the same storm and the same sprite from two different locations.”

They captured around 10 sprite images from both locations, despite the challenges associated with such a feat.

“Explaining to the other guy which part of the empty sky to point the camera at can be quite difficult,” he says with a laugh. “This is especially true at the SKA site, where we aren’t allowed to use wifi or mobile phones, so communication is really difficult.”

These bistatic measurements allow SANSA researchers to determine the precise location and altitude of the sprite. If they can match that with the parent lightning strike that caused it – using the South African Weather Service data or data from their electrical field receivers – they will better understand the precise relationship between sprites and lightning strikes.

When not watching for sprites, SANSA’s OSR laboratory hosts a number of cameras and other instruments that watch the sky, especially focusing on the upper atmosphere.

There is a night vision camera and a Fabry-Perot interferometer, both of which detect and measure changes in upper-atmosphere airglow. The camera contributes data to the study of atmospheric gravity waves, while the interferometer provides data for a global model of winds in the upper atmosphere.

These winds affect low-orbiting satellites, so being able to predict wind conditions 240kms above the surface is economically very important. The OSR laboratory hosts the only instrument in Southern Africa (and one of only three in Africa) that contributes to this global model.

When not watching for sprites, SANSA’s OSR laboratory hosts a number of cameras and other instruments that watch the sky, especially focusing on the upper atmosphere.

There is a night vision camera and a Fabry-Perot interferometer, both of which detect and measure changes in upper-atmosphere airglow. The camera contributes data to the study of atmospheric gravity waves, while the interferometer provides data for a global model of winds in the upper atmosphere.

These winds affect low-orbiting satellites, so being able to predict wind conditions 240kms above the surface is economically very important. The OSR laboratory hosts the only instrument in Southern Africa (and one of only three in Africa) that contributes to this global model.